Race to Bonita

July 29, 2012

Mack Bishop

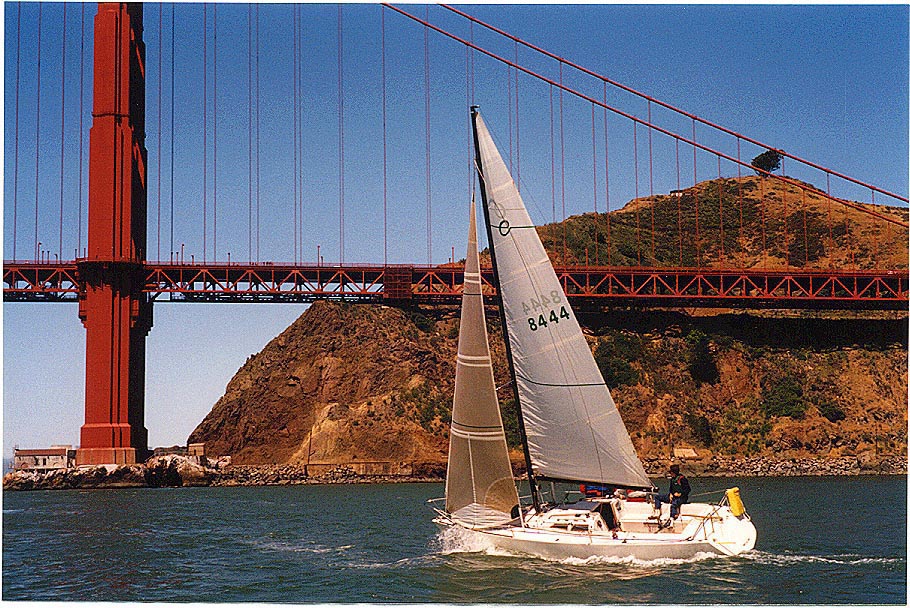

Summertime sailing under the Golden Gate is a high wind experience with strong current and rolling ocean swell. Sailboat racing in these conditions brings urgency and hopefully good seamanship, for their is a necessity to undertake some crazy maneuvers to get out the ‘Gate’ and back within the safe confines of San Francisco Bay.

Golden Gate Sailor

July conditions are predictably strong and gusty winds extending from Alcatraz to outside the many miles outside the GoldenGate. Beating to windward, (upwind) between Alcatraz and City front, requires driving skill and deep concentration for long periods. The waves get bigger as one approaches the Golden Gate, the helmsman must concentrate on each wave, each gust of wind and helm accordingly. Under the bridge, that gorgeous art deco span, moderate ‘bay size’ waves give way to ‘ocean swell’, those moving humps separated by troughs. Wind formed waves form on the top of each swell, where multiple waves form a waffle pattern on the rolling humps. The helmsman must keep their boat pounding forward to overcome these powerful moving obstacles.

Past the Golden Gate at Mile Rock tower, seas become turbulent from swell bouncing off the cliffs and rocks within the grand amphitheater formed by Point Bonita, Lands End and Golden Gate. Between Bonita and Lands End the breadth is open to the ocean with those swells funneling in with nowhere to go but bounce back, into the oncoming rollers. Refracted waves from shore get tumbled with oncoming rollers to create pits, big waves and occasional walls. Perhaps fifteen feet high, regulars are seven, one can spot the moving wall about fifty meters off. “Big Wave fifty meters” goes a crew holler, “big wave, big wave” comes an urgent call from another crew. “Head up, head up, head up”, a first mate would typically bark during the final seconds before climbing the wall. The sloop must attack straight on with speed, where she climbs easily, otherwise get ready for rock-and-roll.

After cresting a big one, “head down, head down”, is the common refrain from everybody, even though the helmsman knows what to do. Heading down means change direction briefly to get more push from the wind, “scoop up more wind”, before heading once again in the intended direction. This “powers up” the boat, re-establishing forward momentum in preparation for the next set of rollers. the direction that one wishes to go. Down for power, up for speed and head straight into that wall. The boat will “climb on up” and power down into the trough, sometimes with a slam plunge. Up the swell directly, down the backside at an angle. It takes practice.

Point Bonita is the gorgeous turn-of-the-century lighthouse with the iconic mini-suspension bridge that extends out to the lighthouse point. Bonita Buoy is the shipping channel buoy rocking and gonging constantly from the roiling seas. Our boat and alls the other racers pound fervently toward that lonely green sentinel, patiently ringing at sea. No one would ever do this by choice would they? Our crew is jumping and working, white knuckle gripping and talking through the wild moments we are sharing.

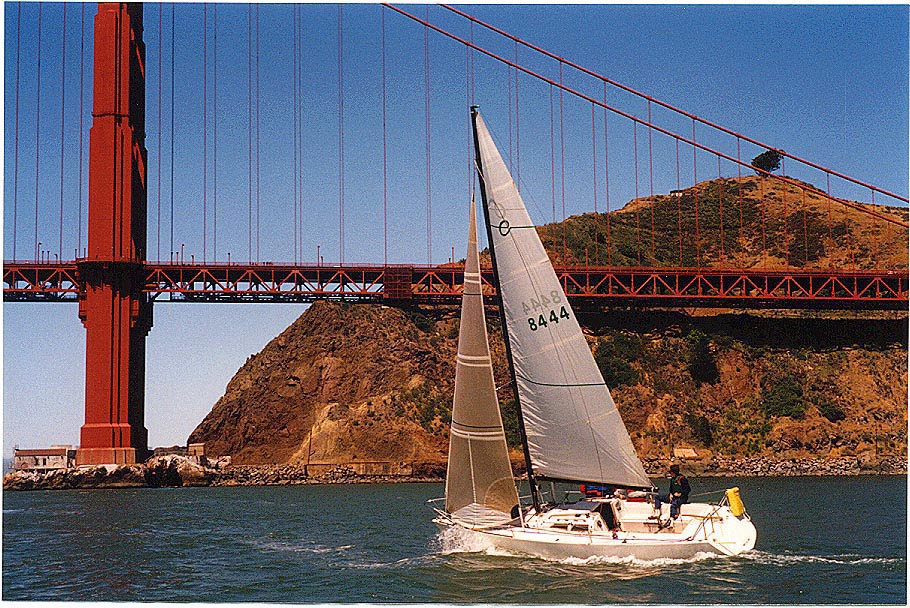

Rounding the floating green tower to port we begin the task all have been waiting for, sled ride back on those swells. Downwind sailing is completely different being smooth, fast and in high winds sometimes scary. Spinnakers are the big colorful sails that look like parachutes. Hoisting and setting spinnaker in high winds is a wild moment. The rigging takes great care to avoid problems. The crew must raise the spinnaker quickly because the sail fills quickly and the sail becomes almost impossible to raise afterward. The “kite” almost pops open with a snap-crack and controls lines become taut in a second. After she pops open, or does not, there are a few long few moments of silence among the crew, all are looking up. All aboard seem briefly mesmerized by the size and power of the beast. Turn the wrong way too quickly and the boat goes over hard, not capsizing but leaning over scary hard. The sailor feels the speed change viscerally, like on bicycle going downhill, with the added dimension of raw power tugging, pulling and jerking a six thousand pound boat with five people like a child’s toy.

Spinnaker in Big Waves

Our “set” was clean and we began to shoot toward the Gate in the same direction of those ocean swell “rollers”. Now the fun begins. The boat is scooting along “at speed” while getting shoved around pretty good by gusts. Traveling faster than the rollers, our sloop catches up with one of those walls, and occasionally a power gust will arrive at the same moment. This is the moment sailors wait for, it is nearly impossible not to scream as the boat leaps off the wall, the hull flying hull out of the water, only the ‘blade’ and rudder knifing through the water. A hard rudder movement at this moment is devastating, so we just hold course and take air.

Weightlessness, with a barely-in-control moment of planned chaos, such as powder skiing or planing dinghies. Surfers know. In bigger boats, (our boat is 27 feet) big wind and waves are needed to deliver that airborne weightlessness moment. Sometimes sustained a powerful ride can last ten seconds. These moments reminds one they are alive, fragile and powerless. The preciousness becomes crystallized, going to that edge of control under chaotic conditions, propelling your little teacup through waves, wind and traffic.

The wilderness feels close just one mile outside. All around one sees boats, but they really cannot help if something goes awry. Sailors cannot see another boat when they disappear in a trough, just a sail. A serious danger is a ‘man-overboard’ moment because a person can be quickly lost in the troughs between swells. One can radio contact Coast Guard for search and rescue, but boat and crew is actually very much alone on the water and must adopt a survival approach to such a moment.

Entering Golden Gate under spinnaker causes a few moments of concern. Spinnaker sailing going straight is a workable proposition, but turning is a complicated maneuver that is executed with the motor running. One cannot “unload” the wind from the sail temporarily to perform the “gybe” turn. The crew must instead unhook-turn-hookup the spinnaker with the sail powered up and pulling. Sometimes the big spinnaker gets twisted in an hourglass, throws the rigging around or causes the boat to turn uncontrollably.

All the race boats converge to the one-mile wide gap between South Tower and North Point shoreline. Freighters clearly have right-of-way, (they even look big from a mile away) and steam right through our race fleet while boats are directly under the bridge. The currents swirl and winds change direction constantly, bouncing off land, other boats and the South Tower, destabilizing directional force. Racers are holding on and headed straight downwind with spinnakers flying when the ‘Cap Yuhan’ freighter, loaded with container boxes, announced her intent with a sustained horn blast, vibrating your body.

Hard Knockdown

Even from a mile away the urgency to plan our gybe is palpable. The converging distance is alarming, and problems are common in a gybe maneuver. One does not want to become an obstruction to a freighter, which cannot stop or turn, but only slow down, a little. A race boat directly under the bridge, three minutes ahead of us and closer to the approaching freighter, initiates her gybe and quickly encounters problems. The problems are immediate as the spinnaker torques the boat uncontrollably left and right, then over hard – deck almost vertical. The crew struggles to settle that bucking kite while the boat stays hard over, but nobody fell off. Cap Yuhan is piloted inside the bay by local harbor pilots; she seems to yield speed, while we buzz up and past our competitor. We beat those guys.

Wind funnels through the Gate and explodes with force after clearing Fort Point. The large area bounded by headlands outside the Gate funnels wind toward the narrower bridge towers; the force increases considerably under the bridge because beyond that point the space is unconstricted by headlands. Our boat, ‘Take Five’ makes progress to inside the Golden Gate where the swell flattens and we pull off our gybe between wind gusts.

The new starboard tack is a long straight run with a wide steering angle. The crew hunts for the maximum angle of incidence powering the big kite, waiting for the inevitable gust that propels the boat to double speed in seconds. Wind pressure is consistently twenty with gusts up to thirty, pulling us from seven to twelve knots in seconds. The ‘apparent wind’, all about you, creates an airborne sensation as the boats lifts and lurches forward.

Following Take Five’s successful gybe maneuver the boat transforms to a sled pulled by the funneled force from the Golden Gate. This area is known locally as ‘the slot’. We rip past the Presidio, Maritime Park, Palace of Fine Arts, marina, City front and piers to Yerba Buena, the parade of one hundred racers rip trails of frothed water to YBI.

The remainder of the race is all positioning and finishing tactics. Sailboat racing is highly competitive and even fourth versus fifth is a goal. Racers struggle to gain and hold position during final leg of all race. However, finish is secondary to the action fueled by racing. Sailing west from Alcatraz out the Golden Gate, and coming back, is a world class sailing experience. So fortunate the San Francisco sailor.